everything is about codes

on hidden and not-so-hidden codes.

Through our clothes, we portray who we are to the world, whether we like it or not. Every piece of clothing carries an idea, which we are consciously or unconsciously communicating. Each is embedded with codes, and we embody them in how we dress.

In that sense, fashion is not random. It is a language composed of references and choices that are readable only to those who understand such codes. The difference between knowing and copying lies in the act of decoding. We read and respond to cues, instinctively decoding them while writing our own style in return. To dress with purpose is to edit your own language, rewriting codes until they feel like your own.

Such codes are everywhere. Each fashion house has its own, refined season after season. Their codes can range from a centenary logo and monogram to a design ethos characteristic of the brand. Among the most significant and evident examples is Chanel, which has multiple emblems as part of its codes: chains, pearls, and interlaced Cs. Likewise, Louis Vuitton’s monogram is instantly recognizable to both those who love fashion and those who don’t. But codes aren’t confined to the runway. Each wardrobe has its own set of codes. The more we refine them, the more we understand ourselves and our sense of style.

Yet in the age of Instagram and TikTok, the act of showing off has changed. With social media normalizing it, logos have become a shorthand for community. This quality has remained constant over time, even as bold logos come in and out of fashion. Logos are codes shared among groups of people that align the wearer and the observer through language.

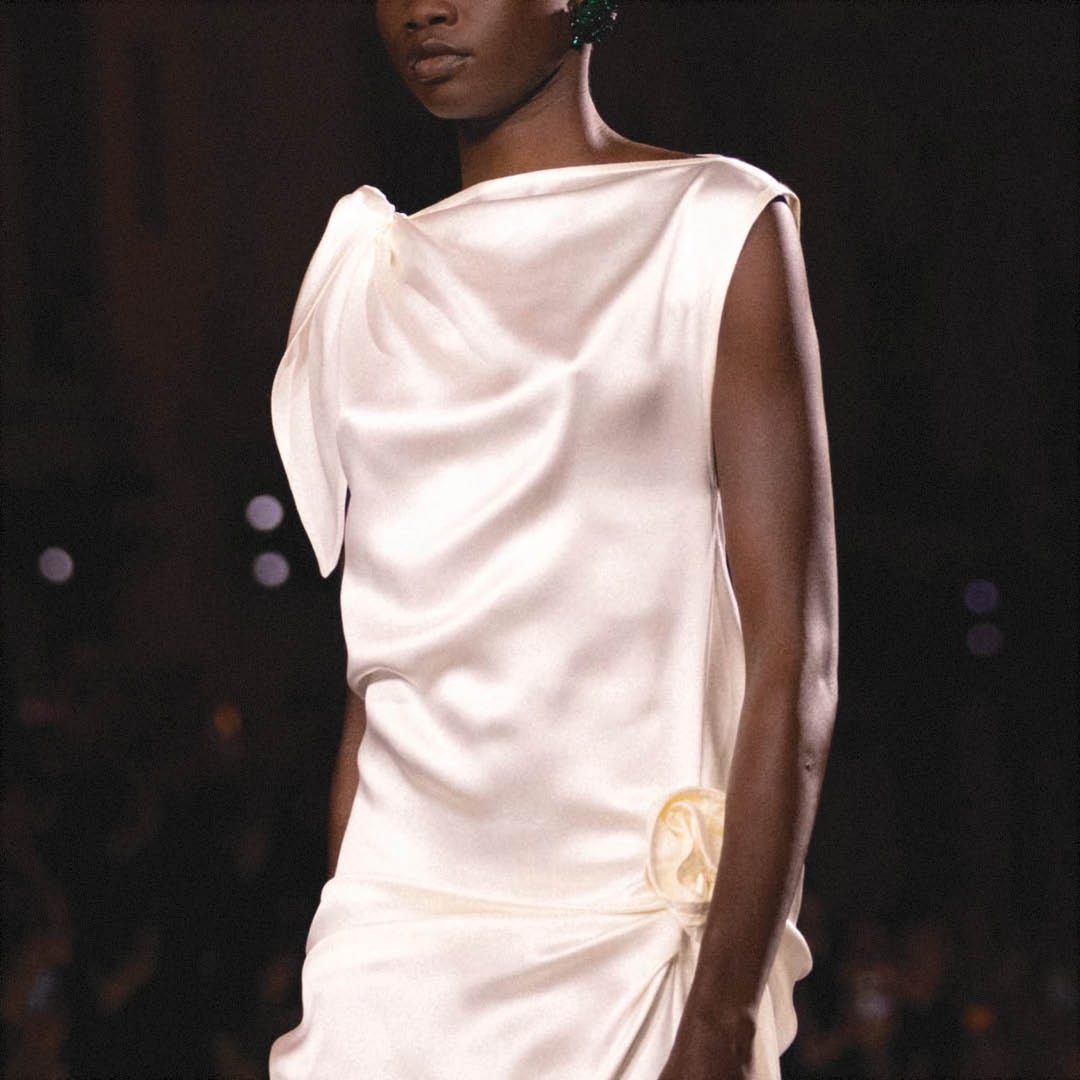

But even more than community, consumers today seek authenticity through minimal, modern design. As fashion literacy grows, so does nuance. More people “in the know” have led houses to seek exclusivity that cannot be purchased through obvious references alone. The new logo is the ability to recognize a piece only by its cut and fit. When everything is exclusive and expensive, nothing really is. People now look beyond surface — silhouettes, color palettes, craft — to identify codes.

Additionally, logos are as good as the clothes that carry them. The Chanel logo was once ordinary; under Karl Lagerfeld, it became chic. (With Matthieu Blazy as artistic director, however, the logo tends to once again become more subtle.)

Still, not everyone wants to be seen. Hidden codes may be as subtle as a seam in the back of a T-shirt, an intrecciato weave, or four white stitches. Whereas logos and monograms place more emphasis on the brand itself, minimalist codes place more emphasis on the product. After years of hyper-visibility, the most desired thing is to be incognito. Minimalism, however, does not mean ordinary — it suggests a knowingness shared only by those who can read the code. No status signaling has become the new status signaling.

Over the past few years, as minimalism has taken over the runways and streets, we have seen a shift toward a subdued aesthetic. Leading it are four designers: Phoebe Philo, Matthieu Blazy, and Mary-Kate and Ashley Olsen. By creating simple designs with intricate details and exquisite craftsmanship, the designers have updated fashion’s vocabulary, creating ubiquitous designs that rule modern fashion. Now, fashion is ruled by attitude more than by silhouette. Whereas once fantasy was coveted in fashion, now it’s reality.

Like everything else in the 2020s, fashion relies on subtlety and secrecy. However, minimalism is nothing new. The same thing happened from the eighties to the nineties. While the former was characterized by exaggerated designs that screamed, the latter was characterized by understated silhouettes that whispered. This can be considered a kind of reverse snobbery, in which one values subtlety over spectacle. It is, nonetheless, a sign of the times.

What was once focused on the clothes is now focused on the wearer. In this way, we can express individuality rather than simply belong to a community that dresses the same way. At the same time, there is a new responsibility for the wearer: to put all their personality into dressing. When every piece of clothing looks similar, the onus is on the wearer.

Over the past few decades, fashion has been dominated by Zara and others, spreading silhouettes from the runways to stores in a matter of days. As there are fewer ways to decode pieces, their craftsmanship matters more than ever. It is the only way to set apart non-designer clothes from designer ones. And as such, it sets apart people who love fashion from those who don’t. Within the former group, there’s a desire for minimalist designs. The fact that so many people were drawn to Charvet’s shirt at the last Chanel runway show is worth noting. Except for the small label, you couldn’t really tell who designed it.

This is the ultimate status symbol that everybody needs: a luxury that turns to the wearer. It is a piece that pleases the wearer rather than pleases the observer. This is what gives fashion its edge today. However, there’s one risk: fashion houses might lose precisely what sets them apart. When everything starts to look the same, each detail matters more than ever to avoid losing the trademark — the one element that embodies the brand and its clients.

In the end, whether a logo, a monogram, or a subtle stitch, each code contributes to the story that fashion tells about who we are. Those who have taste don’t follow the code strictly; instead, they edit it, make it their own. Because style isn’t just how we dress, it’s what we say without words.